Museums are doing it wrong

And what to do about it. Part Three.

In Parts One and Two of this series, I argued that “great” museums of history, archaeology, and anthropology are mostly failing at their primary goal: educating the public. Here I argue that things can be better, and I suggest principles for how.

Why things can get better

I am fundamentally optimistic about the ability of museums to fix this problem, for three reasons. First, museums have the resources. This could be a time of declining resourcing for museums, but the kinds of improvements I’m thinking of only require a modest collection and some well-designed placards. I’ve been to museums that have really cool technological experiences, like the virtual reality experience at the Baths of Caracalla or the interactive language lessons at Planet Word, but these are the exceptions, not the rule. I don’t think people are disappointed that museums are full of things in cases with placards. The analog experience is part of the attraction.

Second, visitor are willing to do the work. I am perpetually astonished that, inside the magic locus that is the museum, people are willing to read difficult texts while standing up. For all our dismal crises about shortening attention spans, museums have some ambiance that makes people willing to put in the work to learn. So don’t blame the people for being too dumb or unwilling to learn.

Third, I believe curators can change. I hypothesize that the fundamental problem with museums is that curators design exhibits for other curators. In his book Bureaucracy, scholar James Q. Wilson (who I reference in a previous post) writes that, when it’s hard to tell if professionals are doing a complex task well, we use the approval of other professionals as a proxy for success. This is explicitly the case in academia, where academics decide which other academics deserve money and promotions. It is implicitly the case in the law, where judges decide what is “good” law based on what they think “better” judges in higher courts would think.

This dynamic, where professionals appraise each other’s work, is generally a good thing in the case of the law, because it keeps the law stable and buffered from the political interests of the day. I hypothesize that curators also form a professional class, talking to one another about how to do museums. And I say that we should take the power back.

Principles for making things better

Answer the f— question, by which I mean the “fundamental” question. Freeman Tilden, who wrote the National Park Service’s first practical and theoretical guide to ranger guiding, said that a tour should start by answering the first questions people will have. If you’re in front of the ruins of a paper mill on the banks of the Shenandoah River in Harpers Ferry, you need to answer questions like “why do you need a mill to make paper?” and “were there paper mills everywhere in America, or just here?” before you can try to tell any story about who owned this paper mill, in what years, etc.

Start high-level and allow people to dig arbitrarily deep. Here’s an idea: on each placard, have one or two sentences in big text that answers the fundamental question and is suitable for children and adults making a speed run; then medium-sized text for people who want to know a little more; then fine print full of jargon and technicality, speaking to professionals and amateur enthusiasts.

Here’s another idea: every single artifact has a QR code linking to the web catalog entry for that artifact. The web entry in turn has links to other relevant artifacts in the museum as well as resources for further learning. All professional museums have this kind of catalog, and they have a way to link pieces to that catalog. Why not have an intern print out these QR codes and put them in place? It would take them like a day and would improve the experience for so many visitors.

De-emphasize audio guides and human-led tours. I estimate that, in most museums, 5% of people use audio guides and 1% are on some kind of guided tour.1 That means 94% of people are relying solely on placards. I’m not saying audio guides are bad, and there are certainly people who will get more out of the museum because of them, but if 94% of people are only using placards, then you better be sure that the placards provide a really good experience. Guided tours are not the meat, nor even the gravy, but more like 15 grams of caviar.2

Learn from museums for kids. Every time I went to the Museum of Science in Boston, I interacted with an exhibit that children were interacting with, and I also learned or reinforced my understanding of a science concept. Consider the possibility that, if children couldn’t get something out of your exhibit, then it is also boring and difficult for adults.

You’re not an art museum; you can tell people what to think. I hypothesize that, because a lot of art eludes a single, neat interpretation, art museums generally avoid explanatory placards. They talk about the facts of an artist’s life but generally shy away from telling you what an art piece means or how to think about it. Forget about that! You’re an educational institution, not an art museum.3 People need basic knowledge about the objects before they can advance to second-order subtleties and controversies. Ending the exhibit with a little room that says “What do you think?” on the wall and letting people write sticky notes is not empowerment but a sham.4

Display less stuff. More stuff isn’t necessarily more interesting. The displayed artifact is usually the culmination of a learning experience, not the start. Sometimes I can look at a piece and go “wow, what’s the deal with this? Better look at the placard!” But normally my experience is more like “OK, that’s yet another Greek vase.” I need some education about schools of painters or how vases were used before I can look at a piece and so “oh cool, this is just like what they were talking about on the placard!”

Have you ever met someone who has a hobby you don’t share and who then launches into inexhaustible and excruciating detail about it? This is how a lot of museums feel to me. A lot of stuff and not a lot of answering the fundamental question about why it’s interesting.

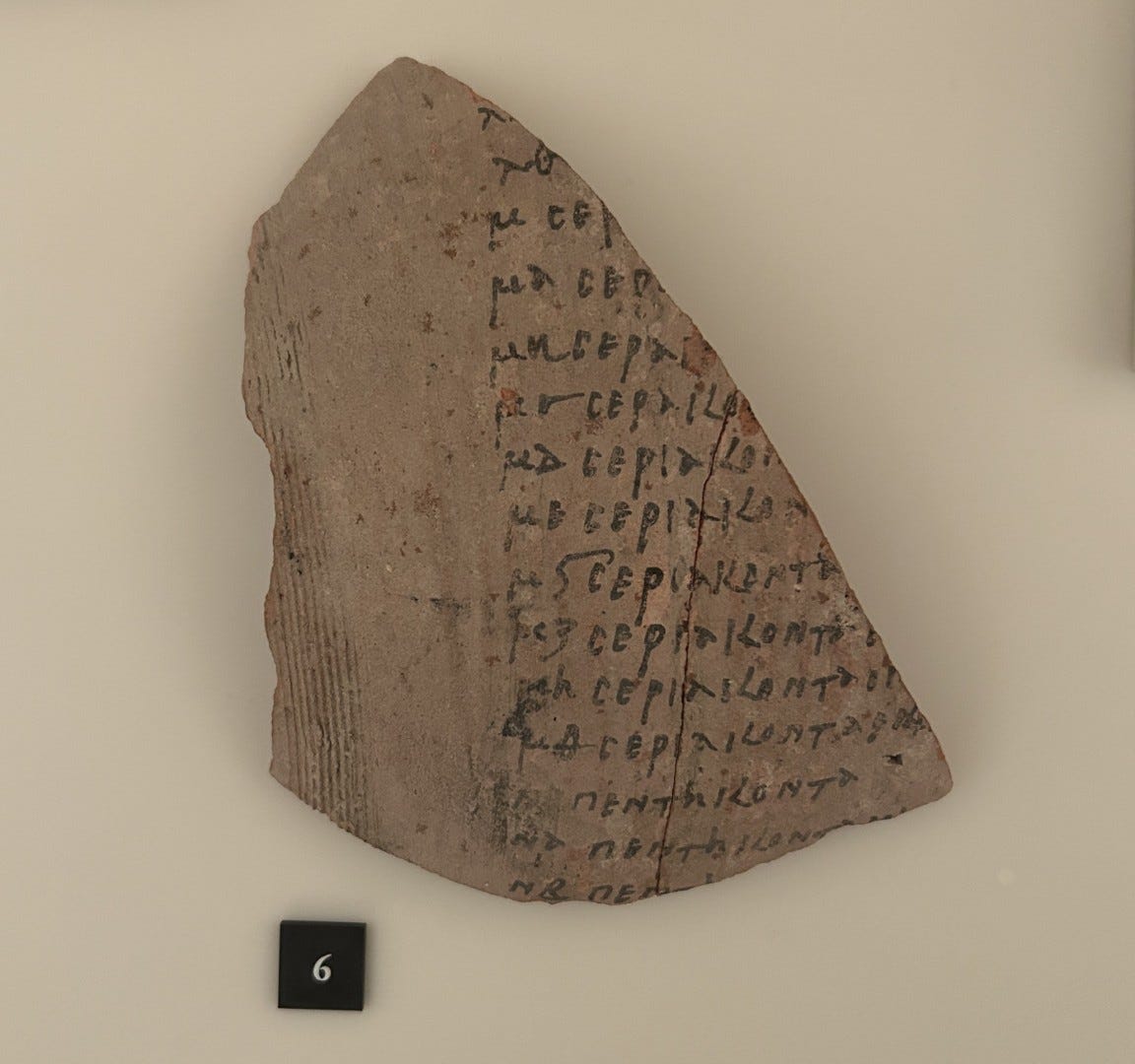

Display the most educational pieces, not the “best” or most beautiful. One of my favorite pieces on my Berlin trip was a broken pottery shard from Hellenistic Egypt with writing on it. This piece is not beautiful or, I imagine, particularly interesting for a professional archaeologist. But to me, it is such a wonderful piece. The writing shows a counting exercise, one number per line, starting with “39 thirty-nine” and ending with “52 fifty-two.” You see the human effort required to learn handwriting, alphabets, and numerals. You see first hand how pottery shards were “scrap paper” at a time when paper (well, papyrus) was rare and broken pottery was ubiquitous. This one unremarkable piece can teach so much about language, the scribal profession, and pottery.

Another example from the Neues Museum: hidden away on the top floor were some pieces of literal garbage, detritus from an Iron Age iron smelting furnace. Again, these are pieces that are decidedly un-beautiful and likely uninteresting to a professional archaeologist. But with good contextualization, it becomes a real gem: this little exhibit was the best explanation of early iron metallurgy I’ve ever seen.

If that sounds boring and useless, let me ask you: have you ever wondered why we humans even bothered with the Bronze Age, when bronze is weaker than iron and the raw ingredients for bronze (copper and tin, mostly) are found in smaller quantities and in fewer places than iron? No? Well, that’s because museums have failed to answer the fundamental question.

If people don’t get the chills, you’re doing it wrong. At Skara Brae, a Stone Age village in very northern Scotland, you go through the museum and through a replica Stone Age house before you go to the actual site. This way, the climax of the experience isn’t just looking at some holes in the ground. Instead, you can actually imagine what it was like to live in one of those buildings, what kinds of relationships you had with the people around you, and what kind of physical objects you used in your daily life. I’m getting the chills just thinking about it.

Here’s a contrasting experience: when I went into the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, the thing that made me really awestruck wasn’t all the golden stuff but instead a piece of circular stone in the ground. This was the omphalion, ancient Greek for “navel.” The Byzantines considered this place the navel, or center, of the world. It’s the spot where, for a thousand years, the Eastern Roman Emperors were crowned. Because there was insufficient contextualization, only I knew that. While my travel companions snapped pictures, I was in a reverie, living through resplendent coronations that happened a thousand years ago.

I suspect this experience is fairly common, that it’s hard to get value out of a museum unless you have prior context. As a friend told me, if you haven’t served on a submarine or watched Das Boot, it’s hard to visit a museum submarine and have much deeper of a thought than “it’s cramped and has a lot of valves.” With a little more context, you can have a terrifying experience. Imagine being a young German man in the 1941. You are conscripted for the submarine service. You leave home, see the ocean for the first time, and go to sea in a submarine. In combat, you are squeezed into a torpedo room, waiting to be told to hit a lever and shoot that torpedo, hoping you aren’t first hit by a depth charge and drown in the dark. To me, it’s almost criminal to just have the dead object sit there, with no attempt to contextualize it.

Help people understand the museum process. How do exhibits get chosen? How do they get put together? Where does the money come from? Transparency isn’t the absence of obfuscation; it’s an active effort to reveal how you work to the people you are trying to serve.

Innovate. I don’t know exactly what needs to be done, only that there should probably be more experimentation.

For example, if you put those QR codes on every piece, then you would passively collect data on how many people read about individual pieces, which would help you know what stuff people find most interesting (or, potentially, most confusing). I’m not saying Big Data will solve museums’ problems, but it is the 21st century, and it’s inexcusable to not be thinking about passive data collection.

Here’s another question: What are other ways, beyond reading and looking, that people can interact with museum pieces?5 I’ve seen a number of experiments here, none of which seems to be a real success, but we should keep trying. (Again, to be clear, I think a little room at the end of an exhibit that asks you to answer “what do you think?” with crayons is a sham.)

I’m not a museum professional, and I’m sure the work is full of all kinds of constraints I don’t understand. But, as a museum-goer, I can say I’m shocked that the overall experience hasn’t changed that much over the past, say 25 years. I’m sure we can do better.

And if you run a museum, oh my gosh I’d be so happy to put my labor where my mouth is. Call me.

There are, of course, exceptions. The Yin Yu Tang House exclusively uses audio guides, presumably to avoid having placards disrupt the historical character of the house. I approve of this use. The Roman Baths in Bath, UK uses audio guides almost exclusively, and I disapprove. Why should I listen to someone read a speech in a flat tone, when that speech could just be on a placard? (For a period of time, the audio tour was given by Bill Bryson, who has a pleasing voice and gave some fun saucy anecdotes about the baths. They’ve since gotten rid of Bill.)

My experience in places like Greece, Turkey, Romania, and Morocco is that guided tours are the norm. You certainly can wander around a site, but usually has little contextualization. I suspect this is the result of a comfortable ecosystem that gives local people jobs doing guiding while freeing the site from building the contextualization infrastructure.

I suspect the art museum vibe is in a lot of museums of history, archaeology, and anthropology because museums grew out of cabinets of curiosities. Cabinets of curiosities crystallize everything I hate about museums: they are a disconnected jumble of artifacts, bound together only by an individual curator’s interests, and explicated only by means of synchronous tour.

If you’re afraid of mis-contextualizing objects, and therefore don’t contextualize them (or worse, assume the visitor has the relevant capabilities and ask them to do it), then you’re falling into the trap of academic historians who get so into their subject and their inability to predict the future that they forget that part of the reason the taxpayer funds academic history research is precisely to help us make sense of the present and future.

Maybe I’m asking why I need to bring my own pencil and paper to do sketches when I do to a museum.

A wise reader pointed out to me that museum curators don't design museum exhibits for other curators, they design them for museum *funders*. The funders are the true customers; you and I are merely metrics.