Museums are doing it wrong

And what they can do to fix it. Part One.

I recently went on a museum-heavy vacation to Berlin. I wanted to visit Germany because the Germans have been key players in classical archaeology. Schliemann is famous for excavating Troy at a time when the Trojan War was suspected to be just a myth. The oldest book from the New World, written by the Mayans, is in Germany. They have a lot of really good ancient Greek vases. I could go on.

I got to see some of those things, but I also got a good dose of museum discontent.

This post is the first in a short series on what museums are doing wrong and how they can do better.

What are museums for?

My first thesis is that the primary purpose of public museums of history, archaeology, and anthropology is to educate the public. Museums certainly have other functions, like doing research and maintaining collections, but those other functions ultimately serve the purpose of educating the public.

This contention elides a lot of complexity, but its value is in contrast: my second thesis is that many, if not most, of the “great” museums of history, archaeology, and anthropology fail miserably at this educational goal.

My experience in most “great” museums is that they are not designed for the public, or even for amateur enthusiasts like me. Instead, I think most museums are designed by curators to please other curators. It is a conversation and competition between members of a profession, and any exhibits that seem to be speaking to “us” are a result of that professional conversation, which is, to a large degree, about how people like you and me will interact with their exhibits.

My rational argument

Think about the last time you walked into a “great” museum. You were likely awed and overwhelmed by its vastness. You consult a map, select a destination, navigate with some difficulty to some particular room, and then begin your museum experience.

You probably start by reading a wall of text, squinting and thinking hard, trying to make sense of what the exhibit is about, realizing that you are ignorant about many things the text treats as self-evident and about many things that the text treats as important but you find inscrutable. You then proceed to Look At Objects, each of which has a little placard that tells you very little that helps you know what to make of it.

Now, think about how it would be if you had a friend or teacher who wanted to educate you about the same topic. Where would they start? What questions would you ask? What things would help you learn fastest and most deeply?

I hypothesize that the things you would want to see and hear have almost no overlap with the things you saw in the museum.

My mini-screeds

I’d like to share some stories about times when a museum or museum-like experience disappointed me, when there was a missed opportunity for learning. (These stories are not necessarily the best ones to support my rational argument, but they are ones that stand out most firmly in my mind.)

I’m in the Bode Museum in Berlin. It is a vast and beautiful museum, mostly full of Medieval art. I wander around, hoping to find something that strikes my fancy. In one corner of one random little room, my eyes set upon a small, intricately carved piece. It seems special, but the placard merely informs me “Altarpiece, mother of pearl, some time, some place.” I puzzle for a moment. Well, if I can’t learn about the piece, I might as well remind myself what mother of pearl is. So I whip out Wikipedia to read the page on nacre (the technical name for mother of pearl), and on that wiki page, dear reader, the first example of artwork is literally exactly this piece I’m standing in front of. I am stunned. Now I really think this piece must be important, but I have almost no way to figure out if that’s true. So I wander off. The end.

I’m still in the Bode Museum. One of their treasures, highlighted on the map, is a mosaic from a church in the later Western Roman Empire. I hunt it down and am quite surprised by what I see. It looks like an Eastern Orthodox mosaic, and so must be an interesting example of East-to-West cultural flow, which seems to be a theme in some other pieces in this part of the museum (but which is not indicated anywhere). Mercifully, this piece has a placard with some explanation. But what does this placard tell me? About how this mosaic was, at some time in the past, taken off the wall at its original location and then imperfectly reassembled here in the Bode Museum. There is nothing about, you know, art or history.

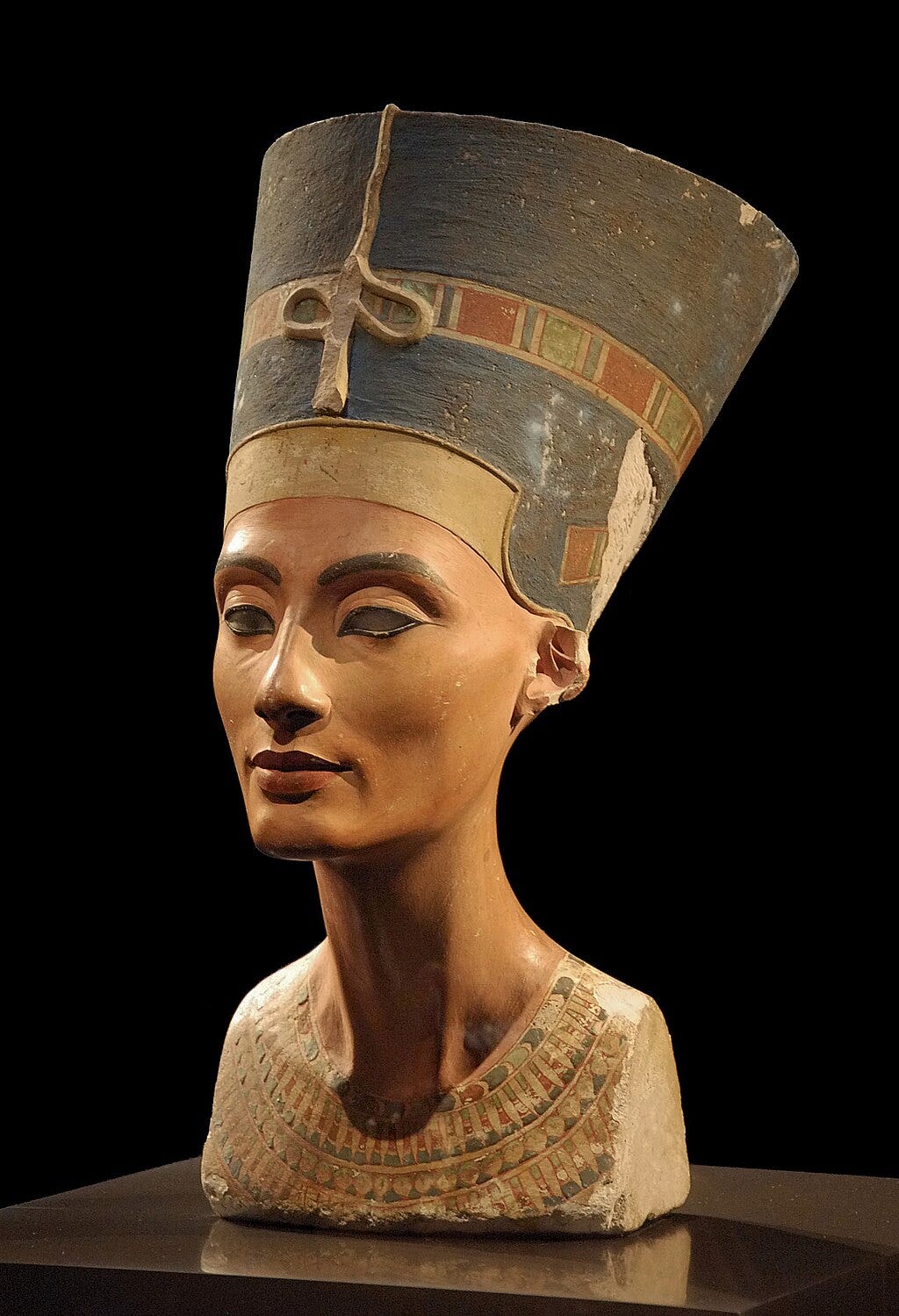

Now I’m in the Neues Museum, whose most treasured piece is the Nefertiti Bust. The bust is closely guarded, in a room all by itself. You can only take a picture at a distance of about 30 feet. (Why? I could guess that it’s about ensuring that photo flash doesn’t damage the pigments, but who cares about educating the peasantry about archaeological conservation? Certainly not this museum.) I walk up close, admire the object, and then read the approximately 150 word placard, mostly talking about how Nefertiti is beautiful but also realistically portrayed (i.e., she has gentle wrinkles under her eyes). This is the museum’s single most prized piece, and they’re just like “Oh yeah, that thing? Let’s give it as much explanation as we do the random stuff down in the basement.”

I climb the stairs to the top floor of the Neues Museum. There are very few people, presumably because of the stairs but also because the first room you walk into is literally a bunch of dark, dusty cabinets. But I’m a nerd so I skim all the placards. I read one and am stunned: this is Virchow’s collection. Wait, that Virchow? Virchow, who I know from my biology and public health background is one of the founders of modern biology and medicine, was also an archaeologist? The placard says something oblique about this “medical career” but nothing else. I consult Wikipedia and find out Virchow was staunchly anti-Darwinist (purely on scientific grounds), anti-germ theory of disease (we would say in modern jargon that he considered social determinants of health the true cause of disease), and anti-racist (in part because of his scientific comparisons of human bodies). This dusty pile of bones in a case isn’t that interesting on its own, and the opportunity to link to this fascinating person is lost.

In the second part, I’ll share a few more screeds and then some actual constructive ideas.

Having also recently spent time in several large European museums, I had some similar reflections. I was struck by how much my experience in these museums resembled my day-to-day experience of browsing the internet: an endless stream of interesting things, each with minimal context, leaving me to search elsewhere to actually understand them. A “vast collection of media with a small amount of context” might have felt novel and worthwhile twenty years ago, but I think the concept could use some updating.

In more traditional museums, I find myself drawn to guided tours, which are more focused and provide the opportunity to learn more without pulling out my phone. I’m also drawn to less traditional museums, which often feel more engaging. On this recent trip, I was most satisfied with my visits to the Museum Het Schip and the Anne Frank House, where the focus was narrow and the setting itself was connected to the material being presented.

Cool post. Totally agree. ChatGPT can really revolutionise the museum experience, take a picture of whatever you’re looking at, get a decent explanation, ask it whatever questions you have. Amazing! However, museums seem to go out of their way to block out signal and not have any accessible WiFi, probably so that people focus on the art. Which is completely infantilising and ineffective, because if people want to mess about on their phones they’ll find a way. Very frustrating!