A portrait in government efficiency

Eula Bingham, Director of OSHA (1977-1981)

If you’ve had a job that involves any kind of physical labor, you’ve probably heard of OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or at least seen its posters. My first exposure to OSHA was in undergraduate chemistry classes, where I learned about material data safety sheets.

There’s some irony in this, because OSHA in its early days was criticized for focusing too much on worker safety, meaning avoiding accidents, and not enough on worker health, which includes things like minimizing exposure to toxic chemicals. James Q. Wilson, a scholar who studied bureaucracy, wrote that this was the unsurprising result an agency being given the choice of taking on relatively harder or easier tasks:

[OSHA] is charged by law with promulgating rules designed to improve worker safety and health. The organizations that pressed for this law were pretty much in agreement that industrial hazards presented a greater threat to worker health than to safety. From time to time workers may be injured by a machine lacking a safety feature or by a poorly designed ladder, but these risks, serious as they are, are not as grave as the prospect of thousands of workers becoming ill or dying as a result of exposure to toxic chemicals. [...]

Given these circumstances, one would expect that most of the regulations issued by OSHA in its formative years would address health hazards. Not so. [...] OSHA has done more to address safety than health concerns. The reason has nothing to do with insidious interest-group pressures or distorted personal values. Regulation-writers find it much easier to address safety than health hazards. [...] A worker falls from a platform. The cause is clear–no railing. [...] The directive is easy to write: “Install railings on platforms.” But if a worker develops cancer fifteen years after starting work in a chemical plant, the cause of cancer will be uncertain and controversial. [...] The solution will be hard to specify: One can write a directive that says “reduce exposure to chemical X,” but [questions will arise, such as] “Reduce by how much?” “Over what length of time?” “With what likely benefits?”

Many factors contributed to OSHA’s slow pivot from safety to health, but I want to draw attention to one in particular: Eula Bingham.

Bingham was an academic chemist who pioneered the study of chemical carcinogens. Her work garnered attention outside of academia, and she went from being just a scientist to a consultant, to an expert witness, to a government advisor to NIOSH, the Department of Labor, the FDA, and the EPA.

In Bingham’s time, the workplace could be very dangerous to health:

At one company, which used benzidine-based dyes, [Bingham’s research group] found that almost half the workers had some form of bladder cancer.1

Bingham reluctantly took on what would be her most important role:

In early 1977, Eula Bingham [...] got an unexpected call from the [President Jimmy] Carter transition team. Would she take over [as director of OSHA]? “I laughed at them,” Bingham said. “I said, ‘I couldn’t do that; I’ve got children.’ I was divorced.” The new labor secretary [...] talked her into it.2

Under Bingham, OSHA began regulating dangerous workplace hazards, things like lead, arsenic, benzene, cotton dust, pesticides, and toxic plastics. As Wilson notes, it’s hard to estimate the effects of these interventions, but they are considered substantial. Bingham gave many years of healthy life to many, many Americans.

“We were turning over rocks all the time,” she said. “Here would be a horrible disease, or people literally falling over. The five years before I went to OSHA, it was just zip, zip, zip, zip, zip. There was so much going on.”

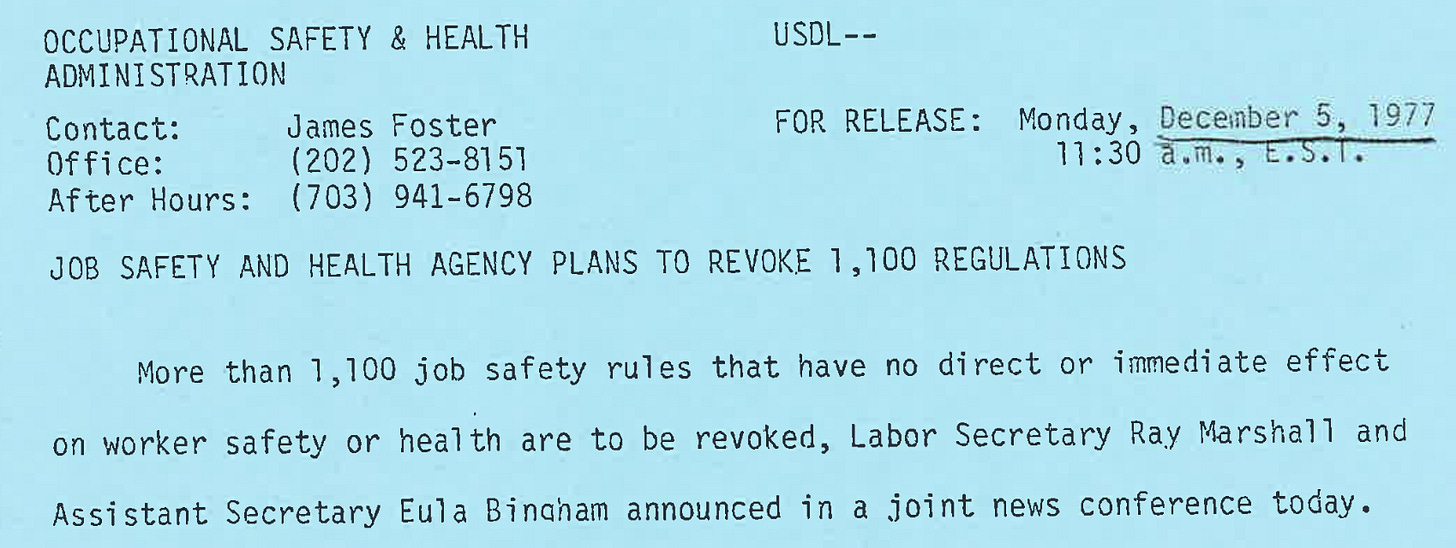

But she wasn’t just pro-regulation. Bingham removed obsolete or ineffective regulations, most famously revoking a batch of 1,100 regulations that included things like the number of loops on workers’ belts, the design of toilet seats, the use of umbrellas to provide shade, and the precise height that a fire extinguisher should be placed on a wall.3 The regulations on the design of wooden ladders was cut from 12 pages to 2.

“We are proposing to revoke these standards to permit OSHA to concentrate enforcement in areas with the highest potential for serious illness and [illegible],” Dr. Bingham explained.4

By reducing the overall number of regulations, OSHA could spend more of its limited inspection budget on more important hazards. By relying on existing, broad regulations against workplace hazards, industry managers could design more workplaces that were both efficient and safe.

Bingham’s legacy is difficult to estimate. Jimmy Carter backed Bingham in most but not all conflicts with regulated industries. Reagan, who succeeded Carter, was very interested in the cost of regulations. Reagan’s OSHA reversed or refined many of the workplace health standards set in Bingham’s time.

Regardless of the outcomes in OSHA’s health standards, I’m fairly certain that everyone, both “pro-industry” or “pro-health,” prefers an OSHA that wrangles over the cost-benefit calculations of the most important hazards, rather than an OSHA that nit-picks unimportant nonsense. We might disagree about the precise levels of benzene or formaldehyde that should be permitted, over what timescales, but I’m fairly certain no one wants those 1,100 rules back. This, to me, is Bingham’s greatest legacy, and it’s a lesson for today’s pushes for governmental efficiency.

Katharine Q. Seelye. “Eula Bingham, Champion of Worker Safety, Dies at 90.” New York Times. 23 June 2020.

Jim Morris, Center for Public Integrity. “After 44 years, halting progress on workplace disease.” 6 July 2015.

In my limited research, I found it hard to get concrete about these exact regulations. They are hard to look up, and some of the reporting is about people’s perceptions of what the regulations were about. For example, a regulation saying that umbrellas could be used to provide shade got interpreted as “umbrella mandates.” Some things in this list are likely apocryphal.