There is no such thing as corporate greed

Or, if there is: don’t hate the player, change the game

Some corporations have done some terrible things. Tobacco companies knew –or at least strongly suspected– that smoking caused cancer, but they continued to sell cigarettes. DuPont suspected –and then knew– that some of its products, including Teflon, were poisonous to their workers and to the general public. Wells Fargo stole people’s money. Healthcare companies are now routinely accused of “greed” based on things like drug pricing.

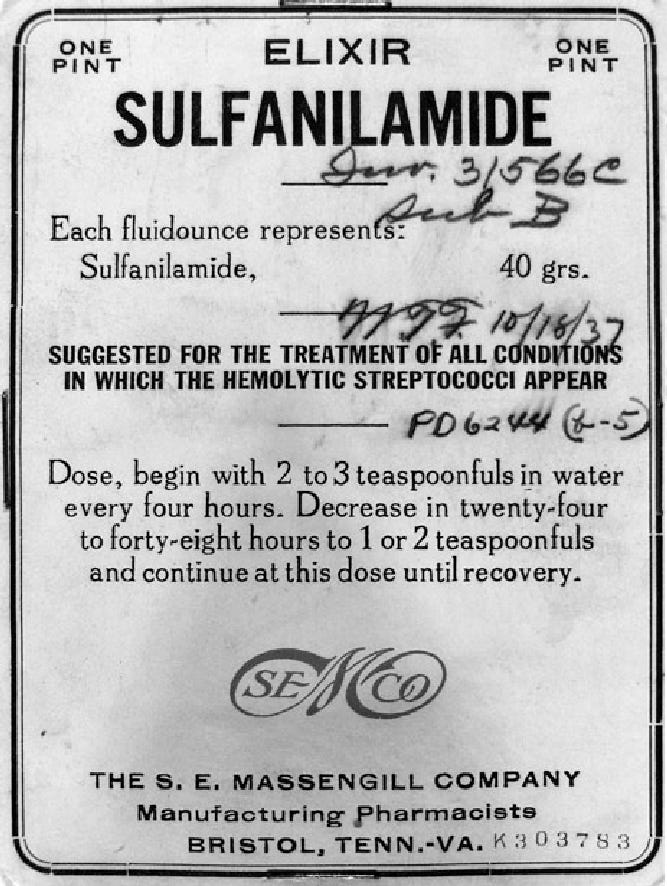

My favorite example of what might be called “corporate greed” is the elixir sulfanilamide disaster of 1937. Sulfanilamide, one of the first antibiotics, had been sold up to that time in tablet and in powder form. Market research by the pharmaceutical company S. E. Massengill showed that some people would prefer to take the drug in liquid form. Massengill’s chief chemist found a liquid that would dissolve sulfanilamide as well as a raspberry flavoring that would allow them to better market the liquid drug to children. In September 1937, after positive taste tests, the company started selling liquid sulfanilamide to the general public.

Within a month, it became clear that many people who took liquid sulfanilamide had died. It turns out that the liquid that the chemist used to dissolve sulfanilamide was diethylene glycol, a deadly poison which we now use as antifreeze. All told, around 100 people died, including many children.

The head of Massengill didn’t really see any problem. “We have been supplying a legitimate professional demand and not once could have foreseen the unlooked-for results,” he said. “I do not feel that there was any responsibility on our part.” The chemist, for his part, committed suicide.

Massengill’s statement that the company could not have foreseen the results was not strictly true. It was not known at the time that diethylene glycol was poisonous, and unsophisticated animal testing might not have revealed this. Slow and careful human testing, like we do now for new drugs but which was not expected at the time, would have caught this effect.

Massengill’s statement that the company bore no responsibility was also legally false. There were many civil suits against Massengill, and the company had to pay money to people it had harmed.

Clearly, Massengill took actions that killed children. I’m not sure “corporate greed” is a useful concept here. I know what it means for a person to be greedy, but what does it mean for a company to be “greedy?” How would invoking “corporate greed” help prevent another company from doing something similar?

Maybe it seems like I’m splitting hairs, but consider this: while what Massengill seems reprehensible, and although they were subject to civil penalties (i.e., they got sued), they had almost no criminal liability. At the time, there were no requirements for safety tests before selling a new drug to the general public.

In fact, Massengill could only be prosecuted for a single crime: mislabeling. The company labeled their product “elixir sulfanilamide,” but “elixir” was a specific technical term for a drug that has been dissolved in ethanol. Technically, Massengill had produced a “solution,” a more general term than “elixir” that refers to a drug that has been dissolved in any liquid. For this crime, the company received a fine equivalent to about $400,000 today.

I’m certain Massengill was excoriated in the press and at the dinner table, but thankfully, something happened more than blame or accusations of greed being piled on a single company. Instead, US lawmakers pressed the president to sign legislation that created our modern FDA, which started applying strict safety testing rules before new drugs could be sold to the public. When you take a prescription drug today, you can be assured that an incredible amount of effort went into testing the drug for safety.

In other words, whether Massengill was “greedy” is beside the point. What needed to happen was to change the rules of the game, so that good business practice would include things like animal testing before releasing a new drug. Rather than blame an individual company, we should ask if a company is behaving according to the rules. If so, and we still don’t like the results, then we need to change the rules.

If you don’t like that Apple or Google is reselling your data, but you don’t want to get rid of your smartphone and email accounts, then I think it’s wiser to advocate for privacy protection laws than to say the corporations are “greedy.” Right now the system gives us two choices: become commodities in a data economy, or opt out of nearly everything digital, including many crucial professional and social networks. In this system, it’s clear why we make the choice we do. So if everything is proceeding according to the system we laid out, whose fault is it? If pharmaceutical companies compete to maximize shareholder returns rather than societal good, is it the corporation’s “fault” for not acting charitably, or our fault for not changing the system? We should not expect organizations to demonstrate healthy, law-abiding self-interest and then call it greed.

Furthermore, I’m not even sure what it means for a corporation to be “greedy.” I know what it means for a person to be greedy, to further their own interests in a way that harms others. A person can use a corporation as an instrument of their greed by, say, breaking laws. And clearly a group of people could be greedy. If a corporation is made up of ten people, and all of them are greedy, that group of people is greedy. But what does it mean for the corporation per se, apart from the people who compose it, to be greedy? A corporation, as a legal person, can be legally accountable for the behavior of its human employees, but what would it mean for greed to exist in the corporation, but not in the people who make up the corporation?

Philosophers debate the concept of “collective responsibility,” the idea that moral blame can lie outside of individuals humans but inside groups of humans. In some cases, this idea might feel self-evident. It feels reasonable to blame corporations and nations, which are well organized and have clear decision-making systems that are a surrogate for an individual human’s moral intent.

What about in looser cases? Can white Americans alive today who did not own slaves be held responsible for the effects of slavery? Or, consider a hypothetical group of bystanders in a village who see an innocent person get stoned to death but have no power to stop what’s happening. Are they responsible for not anticipating the stoning and organizing a resistance?

Again, some corporations have done some terrible things. But I worry that blaming “corporate greed” is mostly ineffective for changing how things work while simultaneously singling out certain kinds of groups and behaviors as morally blameworthy. If we as a society expect corporations to hold to certain kinds of moral compass, then we should probably ask more of other organizations and even entire swaths of people.