Seeing is believing

Covid skepticism, and measles on islands

Covid skepticism took many forms, some uglier than others. I was one of many people in early 2020 making comparisons to the influenza virus. I’m not proud of my ignorance, but I am sympathetic to my past self. What led me to assume that things weren’t going to be as bad as they were?

I have the same curiosity about other kinds of skepticism and denialism. What led people to downplay or disbelieve the severity of pandemic, even when it was in full swing?

The obvious culprit is political. But I think some people had a hunger to see things with their own eyes. Natural disasters like a hurricane are easy to wrap your head around. You can see a news reporter out in a storm, and you can see on a map who is going to get hit, and how hard.

Covid was different. There were official statistics, and there were reports of hospitals being overwhelmed, but if you weren’t on the front lines, or if you didn’t have a person close to you in a hospital, you might not have “seen” what was going on.

I think this hunger to see for oneself is part of what motivated the videos of “empty” hospitals. Someone would come to a hospital and take a video, showing empty rooms or empty corridors, and post this online as proof that Covid was fake or at least overblown.

These videos are almost always misleading. A skeptic might have expected that, if a hospital were “overwhelmed,” that there would be patients stuffed in the hallways. Finding the publicly-accessible hallways nearly empty is proof enough for the skeptic, but a hospital need not be literally overflowing to be overwhelmed.

Some of these videographers could have been cynics, out to create viral content, whether they believed it or not. But I wonder if many of them were honestly confused about a disconnect between their personal experience, maybe an experience where Covid didn’t seem particularly important, and the mainstream narrative that Covid was a crisis?

I wonder if a basic feature of infectious disease epidemiology led to this confusion.

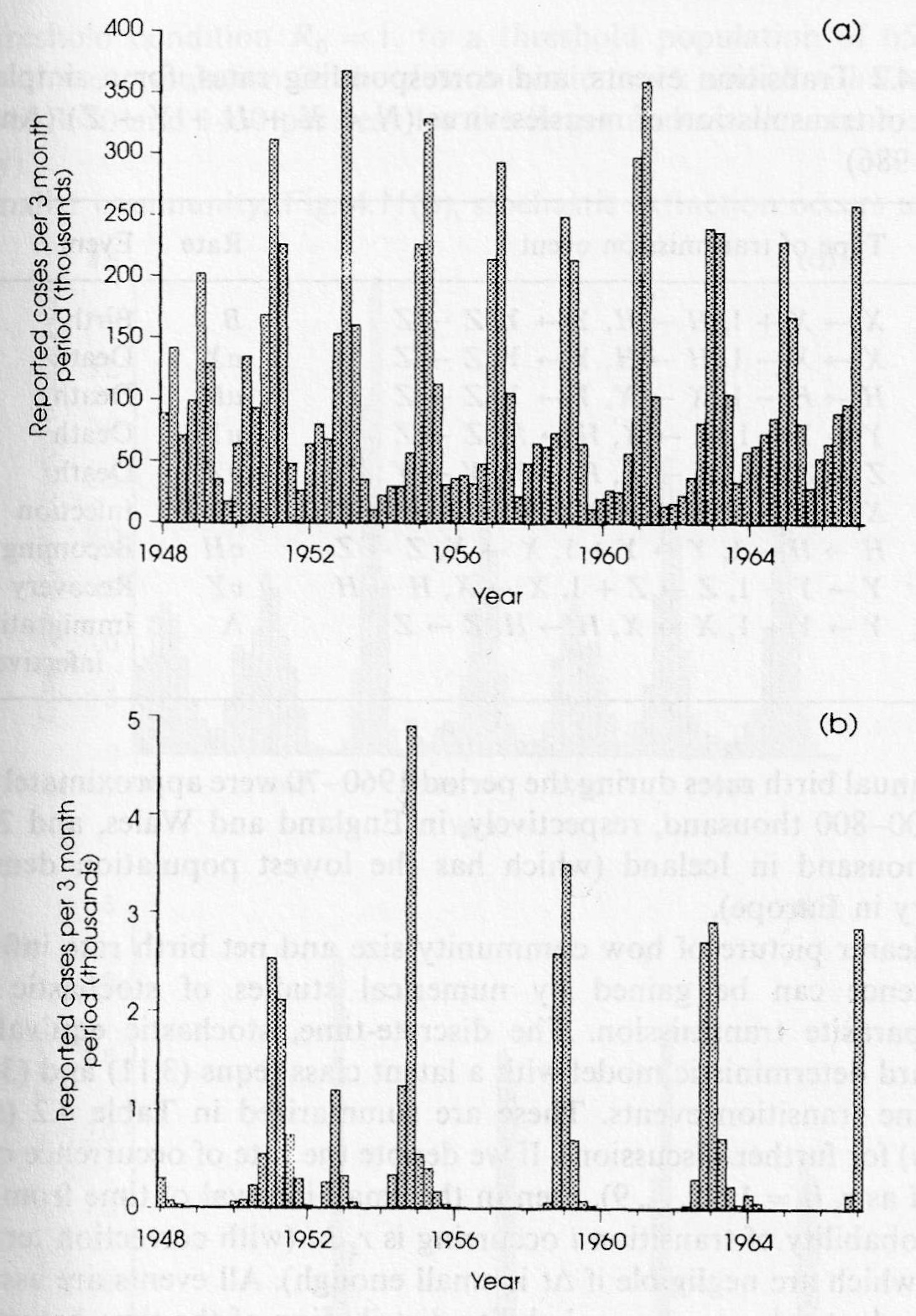

Before the 1960s, when the measles vaccine was introduced, major cities like London had large measles epidemics every other year. This presented a great puzzle to scientists. Was the disease somehow changing every other year?

In fact, this pattern is a result of the cyclical number of “susceptible” children. Say you have a big measles outbreak one winter. Measles is so transmissible that, without vaccination, it could be that 90% of children who hadn’t previously been infected caught the disease. (Before widespread vaccination, measles used to kill about quadruple the number of children who died of chickenpox, and double the average yearly number who have died of Covid. This was more than ten times the number who die now from heat stroke.)

Right after a big measles outbreak, you wouldn’t have a second one, because there simply weren’t enough children who could catch the disease and spread it widely enough. Measles would smolder but not burn.

But after a second year, enough new, measles-naive children had been born that there was sufficient critical mass to cause a new outbreak. The balance between birth rates and disease transmissibility created the observed, two-year pattern.

Outside of large cities, however, there were different patterns. While London had a clear every-other-year pattern, Iceland had outbreaks more sporadically, usually on a four-year cycle. Smaller islands had even less frequent outbreaks. On a medium-sized island, measles would infect all the children and smolder, but it took more than two years for enough new, measles-susceptible children to be born, to create critical mass for a new outbreak. On very small islands, measles would go locally extinct, and new outbreaks would only happen when it was introduced from the outside.

In short, the smaller the population, the more sporadic the measles outbreaks, and the more time that would go by between outbreaks.

This result is even more striking when you add more data points by looking at relatively isolated towns and cities, rather than at exceptionally isolated islands.

Indeed, throughout most of human history, most people lived in relatively isolated groups, villages, or small towns. This meant that infectious disease behaved more like the measles “island” pattern: when a disease was introduced, it infected everyone, and then when everyone was immune, it likely wasn’t heard from for a while. (Some pathogens evolved so that the human body wouldn’t develop immunity. Before antibiotics, people would be infected continuously. Gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis are some familiar examples; yaws is a less familiar one.)

I suspect that many people experience this “on-off,” island-style pattern of Covid. If one person in your family was infected, multiple people might have been infected, and probably many of your friends were too. On the other hand, if you didn’t have Covid, and no one in your family did, and you lived in a small town, it was entirely possible that no one in a decent radius of you had Covid. In contrast, if you lived in a big city like London or New York, Covid would always have been front of mind, because it Covid would never go locally extinct in such a dense population.

And I can see how, if you are hearing on the news about how bad the Covid crisis is, it would be very confusing if, purely locally, things were going along just like normal.

It’s as if little tornados were constantly touching down across the world. If you hadn’t had a tornado in your town, it might have sounded very strange to hear that there was a global tornado crisis, when you couldn’t see it with your own eyes.