Oral history and archaeology

Lessons from The Lord of the Rings and the Iliad

When I watched the movie The Fellowship of the Ring, one of my favorite characters was Galadriel. She was very helpful but also very spooky. She seems very concerned about Sauron, but also not willing to do anything herself right at that moment.

But just as quickly as the hobbits come into Galadriel’s forest, they are sent along their way. We the audience see things through the hobbits’ eyes. Galadriel is yet one more powerful but subtle thing hiding in Middle Earth.

If you read Tolkien’s Silmarillion, you learn more about Galadriel. When she meets Frodo, she is about 10,000 years old. She was born on another continent, the place where the gods live, before they had put the sun and the moon in the sky. After studying with some of the gods, she helped lead a rebellion against them, and that’s why she’s in Middle Earth. All the other elves in Middle Earth that were older or more powerful than her have either gone back to the god-continent or have been killed. Even Elrond, who seems pretty badass, is only 8,000 years old, and he was born in Middle Earth.

If you know this history, Galadriel is less mysterious but more awe-inspiring. Here is a being who probably encountered the evil god Melkor, who is now banished, face to face. She knows that Sauron and Gandalf came from the god-continent and are something, cosmologically speaking, like angels.

Elrond has learned much of what Galadriel knows second-hand, but she was there, and she’s seen it all. In Middle Earth, the wisest and most powerful beings are also the oldest. They know the most because they’ve seen the most.

In Tolkien’s universe, humans “awakened” long after the elves, but even very shortly after their awakening, they had forgotten their origins. When an elf king first finds humans, “he questioned [the human king Bëor] concerning the arising of Men and their journeys, Bëor would say little; and indeed he knew little, for the fathers of his people had told few tales of their past and a silence had fallen upon their memory. ‘A darkness lies behind us,’ Bëor said; ‘and we have turned our backs upon it, and we do not desire to return thither even in thought.’ ” These were the good humans who fled from the evil god Melkor. Others stayed back and worshiped Melkor; their descendants are the evil humans who show up in The Return of the King.

Tolkien’s stories are full of dragons and wizards and impossible battles, but his bit about humans and oral history rings true. I’m reminded of how Homer wrote the Iliad hundreds of years after the Trojan War (if the Trojan War actually happened).

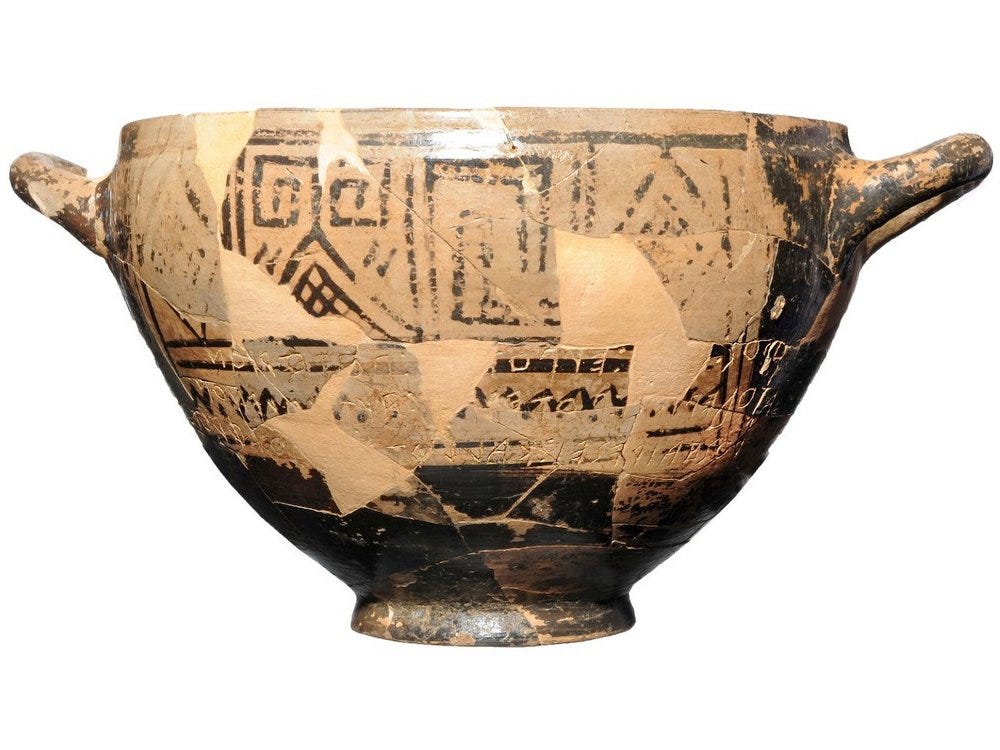

The historical Trojans were a Bronze Age civilization, like the Minoans on Crete. Homer was a classical, Iron Age Greek. Between the Trojans and the classical Greeks came the Greek Dark Ages. During this time, the Bronze Age civilizations around the Mediterranean mostly collapsed. Bronze Age writing systems were abandoned and forgotten. The entire structure of civilization changed: Bronze Age societies were typically highly stratified, with ruling elites taking in and redistributing goods in their central palaces. Classical Greece was still stratified –the ancient Greeks owned slaves and thought slavery was a natural condition– but it was also decentralized and egalitarian enough to eventually produce early democratic government.

Many things in the Iliad are clearly fictional: gods and quasi-divine heroes are center stage. But some pieces seem historical: people fight using bronze weapons and chariots, and most fighting seems to be about small clusters or one-on-one duels rather than large infantry engagements.

It’s remarkable to me that almost any historical fact made it through the Dark Ages. According to Greg Woolf’s Life and Death of Ancient Cities, there’s a general rule of thumb that oral history does a decent job of recording the events of three generations, but things between the chronology between the origin of the world and great-grandparents is typically fuzzy. The Iroquois League is said to have been founded shortly after a total solar eclipse, but scholars debate which of two eclipses, 300 years apart, is the most likely date.

Woolf points out that stories like the founding myth of Rome actually gained detail in written accounts as time passed, suggesting that newer and newer authors fabricated and embellished more and more. If the same process holds for oral history, we should expect that origin myths should become more compelling but less accurate as time passes.

Compared to Tolkien’s elves and the ancient Greeks, we live in a remarkable age. With archaeology, our knowledge of the past actually increases with time. Some things, like the details of the Trojan War, we will never know. But other things, like how the Trojans lived, where, and using what kinds of technology, will become ever more clear. In some ways, we know more about the Trojans than Homer did, even though the gap between Homer and the Trojans was only 500 years, while the gap between the Trojans and today is more like 3,000 years.

For the elves, age meant power and wisdom but also haughtiness. When dwarves were trying to take the most precious jewel in the entire world, the elf king Thingol asked the dwarves, “How do ye of uncouth race dare to demand aught of me, Elu Thingol, Lord of Beleriand, whose life began by the waters of Cuiviénen years uncounted ere the fathers of the stunted people awoke?” Thingol was one of the first sentient beings in the world. He married an angel. Then dwarves killed him deep in a cave. Nobody tosses a dwarf.

Hopefully, archaeology can give us power without haughtiness. Civilization and society has been remade multiple times. The cities of ancient Mesopotamia, of the Bronze Age Minoans and Trojans, and of the Iron Age classical Greeks were all cities, but the societies that built them were very different from one another. Knowledge about how we have lived might give us some sense of how we can live.