Fun facts from Ellis Island

That is, Scott went to a museum and wants you to hear about it

I visited Ellis Island yesterday and am now full of fun facts!

12 million immigrants were processed at Ellis Island, primarily between 1892 and 1921. Before 1890, immigration was handled by the several states, principally New York, which was the country’s main port for incoming immigrants. New York state was processing immigrants at a facility at the southern tip of Manhattan, but Ellis Island became the first federal immigration facility because the federal government suspected that New York state was not running the facility up to code and wanted to take things over.

Ellis Island lost importance when immigration was substantially restricted by the Emergency Quota Act and subsequent legislation that ended the era of mass immigration to the US. Furthermore, immigration processing was pushed “upstream,” from Ellis Island and to the ships that people came in on, and eventually to the current system, where immigration is intended to be processed before people physically come to the United States.

The idea that Ellis Island clerks changed people’s names on the spot, either out of ignorance or out of paternalistic goodwill, is a myth. (The NPS placard more diplomatically called it “part of many families’ oral history.”) In fact, the immigration officials carefully cross-referenced the names that immigrants gave for themselves against the names listed in the customs manifest provided by the steamship companies. A mismatched name was a sign that you weren’t who you said you were, which jeopardized your chance of entering the US.

It was very possible that names were misspelled by steamship clerks or that immigrants intentionally gave different names to put on the steamship manifest. Many immigrants also changed their names after entering the US. So yes, immigrants’ names did often change, but they did not change in the short liminal period that people were on Ellis Island.

Most people spent only a few hours on Ellis Island. For an experience that seems to loom so large in the American consciousness, it was generally a quick one. If your paperwork checked out, you weren’t suspected of being a criminal or “likely to become a public charge,” and you weren’t diagnosed with a disease, you were in and out in a few hours.

However, if your paperwork didn’t check out, or you were suspected of being a criminal, or you were, say, a single woman without family in the US, then you were pulled aside. Contemporary immigration law did not allow these kinds of people into the US. Immigration officials literally wrote the letters “SI” on people’s clothes using chalk to indicate to other officials that the marked person needed a “special inquiry.” Most people made it through the special inquiry, and those who didn’t mostly made it through appeal.

All told, 98% of immigrants who arrived at Ellis Island were permitted in. Some were turned around and sent back to their ports of origin, for medical or other reasons. A small number languished in limbo, some for months, as they waited for family to pick them up, or for some clarification of their immigration status. History does often rhyme.

“Picture brides,” which we now more crassly call “mail-order brides,” was a real thing. Watch Brides sometime; it’s set on the ship that is the historical touchstone for this phenomenon.

In some cases, a single woman without family couldn’t leave the island, being likely to become a public charge, so the fiancé would take the ferry over, the couple would get married, and the US government was content that she was a man’s charge and not a public one.

A sure-fire way to get sent home was to say you had a job waiting for you. The US had a law against “contract labor,” to prevent US companies from overtly bringing cheaper immigrant labor into the country. Immigrants had to thread a fine needle, you couldn’t have (or admit to having) a job lined up, but you also couldn’t seem unable to find work, which would make you “public charge” risk.

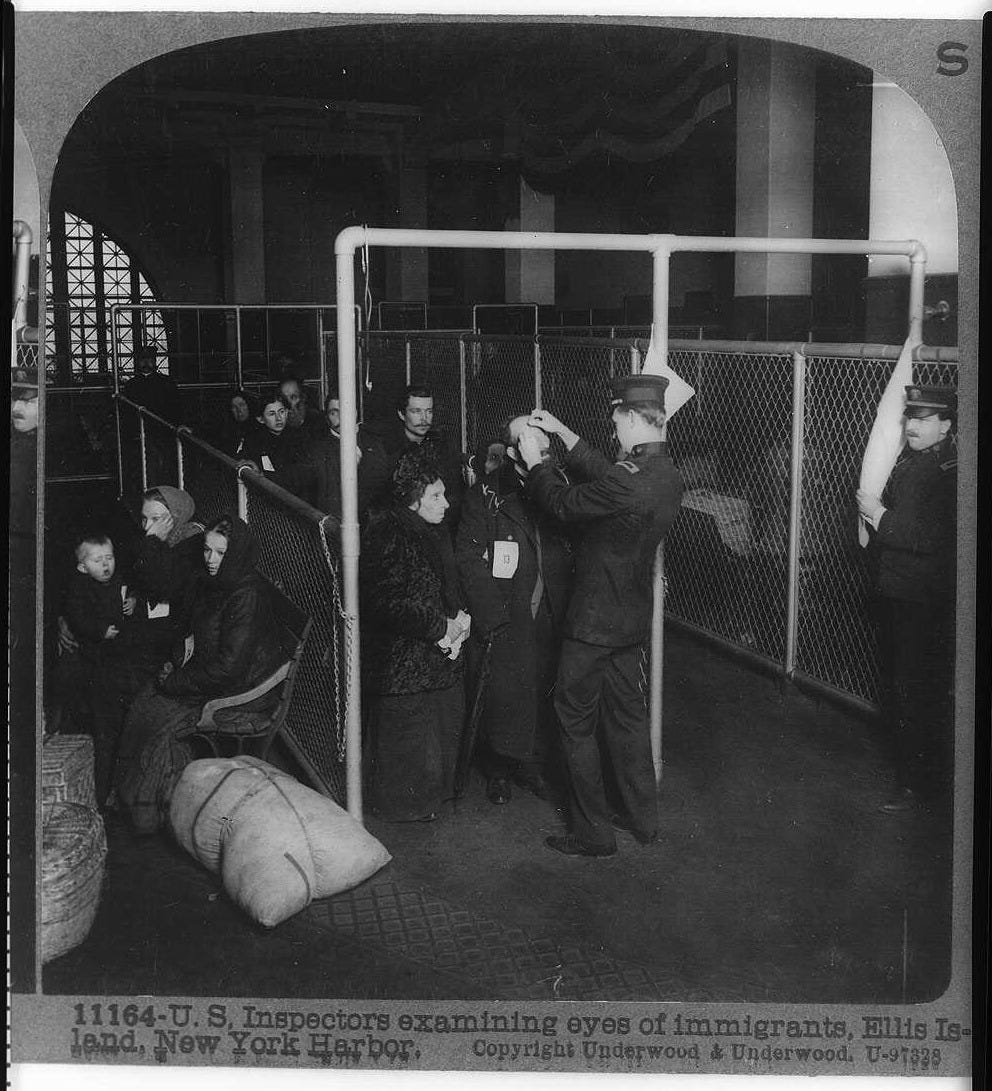

Another way to get sent home was trachoma, a then-untreatable infectious disease that causes blindness. The bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis, the same one that causes chlamydia, can infect the eye and slowly deform the eyelid in a way that causes the eyelashes to scrape against the cornea, which in turn clouds over. Medical inspectors would flip each immigrant’s eyelid inside out, to look for the characteristic bumps caused by the infection. We diagnose the disease the same way today. (Now, a single course of antibiotics can cure trachoma, in the same way we can cure chlamydia, although poor sanitation means that trachoma remains a neglected tropical disease. Don’t confuse trachoma with river blindness, the second-largest cause of blindness after trachoma. River blindness is caused by a parasite that can be effectively managed with ivermectin. Yes, that ivermectin; this is one of the things doctors use it for.)

The medical staff at Ellis Island were part of the Public Health Service, which descended from the Marine Hospital system, set up in the late 1700s to care for American coast guard, naval, and merchant marine personnel. The PHS of the Ellis Island era was a forebear of the CDC and also of the Public Health Commissioned Corp, the “army” led by the US Surgeon General.

We narrowly saved Ellis Island as a historical site. After mass immigration ended and immigrants were processed on their passenger liners, Ellis Island was used variously as a hospital, a naval base, and a prison. It was essentially abandoned in 1955. For about 10 years, there were various proposals to turn it into something super-chic, either very fancy homes or a very fancy marina/resort. The idea to turn it into a park was approved in 1964, but only in 1976 were tourists first brought to the island, and only in 1990 was the site fully reopened as a restored museum, thanks in large part to philanthropic donations.

Clearly I got a lot out of my visit, but I was disappointed that there weren’t more attempts to link the space with contemporary experience. I literally walked the same route some of my great-grandparents did, and stood in the same rooms where they stood, on one of the most momentous days of their lives. That emotional experience was the perfect leverage for me to devour some information about the past, but there was not much attempt, as far as I experienced the museum, to relate those feelings to thinking about immigration in the present.

The museum did have an exhibit about post-World War II immigration, which had a lot of poignant material about the causes of that immigration, but I was literally reading a book on the ferry over about how US Cold War interventionist policies were the root cause of the geopolitical instabilities that caused these heartbreaking situations, and so it was a bit nauseating and I quickly fled the room. It was also down a long hallway, far from the great hall, and the few of us who were down there had the sheepish look of nerds who can’t tell if the bonus hallway full of knowledge they’ve found is actually off-limits.

Nice post Scott. I wonder what part Robert Moses played in trying to turn Ellis Island into a park... I'm currently really enjoying the 99 percent invisible read through of The Power Broker, all about Robert Moses. https://99percentinvisible.org/club/

Have you ever been to the Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site in Philly? I went there w/ my friend Chris recently and thought they did an ok job of connecting 18th & 19th century prison history w/ the present. Heavy stuff.